TIMELESS VIVACITY

Louis <louis09@frontiernet.net> Sun, May 7, 2017 at 6:34 AM

To: maryvolmer@gmail.com

Hi –

Gary Sack is over there on a boat.

I gave him your number.

Lou

Lou is my uncle. Over there is Northern England, where I’m living in a village south of Manchester until August. Gary Sack? No idea. Lou swings with impressive agility between paranoia and complete and absolute trust in oddball, and mostly harmless strangers. So when Gary calls, the next day, and invites me “and the kiddies” to join him on a boat in a canal near Nantwich I say sure, why not? How about Monday?

As a precaution I leave the “kiddy” at preschool, though by now I’ve learned Gary has been Lou’s buddy since college. By mom’s cautious definition, he is a “character,” and though the canal and the boats, and the story I might find, are my excuse, it’s Gary, I’m driving to see.

On the phone he told me to show up “whenever. I’ve got nothing but time,” he said. But, of course, I’ve planned the trip to the minute. I’ll get up early to run, which will leave me time to work after I drop my son off. It should take about thirty-five minutes to drive to Nantwich, and if I leave at noon, I’ll have three hours before I need to be back to pick up the kiddo--who could also be an excuse to leave early, if I need one. I’ll be home in time to grocery shop and scribble some notes before dinner.

It’s a windless mid-May afternoon of sunlight and broken clouds. I shun the M-6 and, putting my faith in the satnav, drive through small towns on unmarked roads, hemmed by hedgerows and newly plowed fields, before parking, on schedule, in a pay lot in Nantwich. A sign proclaims this to be a “historic market town,” but the distinction is boasted, so far as I can tell, by three of every four towns in Northern England. There’s no sign of the canal and the first person, I see, a bald man in a baby blue tracksuit, rushes past me and my inquiry. The second, a woman also in a hurry, red hair perfectly curled, points vaguely north and dismisses me with the same gesture.

On this information, I walk a half-mile away from City Center, past two pubs, a school, countless red brick homes, one like another up Welshmen Road, and nearly turn back. If I hadn’t spotted a small white sign for the marina, I might have; from a distance the marina looks like nothing more than a railroad embankment and bridge. Climbing the steps, I find a curving channel of brown water teeming with boats, most of them long, narrow, steel hulled canal boats, docile as large animals grazing. The few people I see lounging in folding chairs on water’s edge, ignore me effortlessly. They, like the boats, look moored.

I’m supposed to walk toward the chandlery. I could ask the way, but I suddenly feel, even more than I did upon arriving in this country three months before, like a foreigner. I make a lucky guess and walk north up the towpath, following an old fellow and his fluffy mop dog. A young man trims the grass with a terrible roaring racket. Hay and sheep fields unfold in the distance. The lawn mower quits; in the interval: bird song, the hum of a short wave radio, the cathedral bells strike one. And then I see Gary.

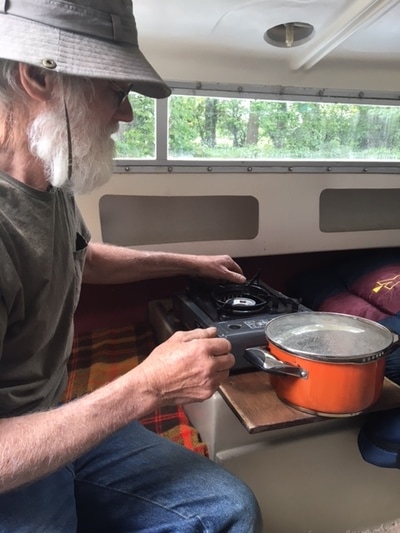

Gary’s boat to be exact, a faded little fiberglass Vivacity 20, all but dwarfed by steel- hulled neighbors. He’s taken the mast off; a solar panel fixed to the cabin roof powers the small electric motor. Inside the cabin is a sleeping bag, camp stove, an orange cook pot, bags of potatoes, onions, rice and beans, bottled water, and a piss pot. “You look like your cousin,” Gary says by way of hello.

Gary might have walked out of the pages of a gold rush history book. He’s weathered and compact, with wiry arms and legs and callused hands. Most of his face is a white beard, a shade lighter than his hair. His eyes, beneath thick scuffed spectacles, are red rimmed, blue and cheerful. Like mine, his voice has the clipped cadence of the American west, but is worn with age and rough as his hands.

Even so, it’s clear that in spite of his accent and the tiny vessel, bought sight unseen for a few thousand quid over the internet, Gary belongs here on the canal. I, by association, have gained some measure of acceptance. In his presence the black man, gray dreads to his knees, on the boat next door, nods hello, as if I’ve appeared out of the ether.

I’ve done a little research, in case I do get a story out of this trip. I know that the canals, a defining feature of the English countryside, were built in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, by landowners and industrialists, to ferry goods from inland towns to major trade and waterways. Today the canals are dominated by well-appointed narrow boats on which you can stay for holidays of up to three weeks. The Fjord Empress, for example, available for L1200-1500 a week through Anderson Canal boats of Cheshire, is a sixty-two foot floating apartment complete with toilet, shower, galley, and wifi (of course). It sleeps six. Other boats promise accommodations for up to twelve, if you don’t mind being stacked into bunkbeds like submariners.

What I didn’t know is that a substantial number of people live year round on the canal. Boat people on “boat time,” with belongings strapped to every available surface. How many is hard to say, since canal dwellers are not allowed, without paying a mooring fee, to dock in one place for more than two weeks. They are required to keep touring. Plus, a number, like Gary, and his dread-locked neighbor, David, are from other countries.

David, a mellow, long limbed man, with dark skin and yellow smile, is from “an island near Jamaica.” He avoids specifics and I don’t press him. There is a feeling of cultivated anonymity about him, and about Eric, a Scotsman Gary stops to chat with as he walks me to the loo by the chandlery. Eric keeps touching his face, as if unaccustomed to the stubble he finds there; he has tousled blond hair, wears sagging jeans and a clean gray t-shirt. He’s been three weeks on the canals, living on this stumpy boat, which is black with blue trim and looks like a bruise. He bought it for ten thousand quid after leaving his job in London. Where he worked? He doesn’t say. How long he plans to live on the boat? He doesn’t know. Who did he leave behind? I don’t ask. His mannerisms are measured and forcefully calm, like some kind of aging Scottish dharma bum. In this age of oversharing, I find his reserve attractive, and somewhat suspect.

Gary is more forthcoming. He’s been on the canal since April. He wanted six weeks alone. His wife, back home in Eureka, California, will join him in June. “She wouldn’t have been happy,” he explains, “roughing it so long.” I suspect he’s right. He takes no uncertain pride in living on beans and rice in an open sailboat cabin, subject to the elements. “You need very little,” he says. “Very little to live.”

Eric and Gary talk electric motors and solar cells. Lulu, Eric’s French bulldog, jumps to shore and pisses on a piling. I might soon do the same, but eventually Gary says goodbye and keys me into a wooden outbuilding with a shower and toilet stall, twenty yards from the chandlery.

A hundred and fifty pound fee gives him access to facilities like this--concrete floored, and clean enough--found up and down Britain’s canal system. The chandlery, also modest, is attached to a shoe box café and laundry facility where Gary introduces Joyce, who runs the place. Joyce lives in Nantwich. “Bunch a snobs,” she says. “I like these lot better. Even the fancy pants.” Reading my confused expression, she explains. “Some of these boats? A hundred thousand pounds to buy. Fancy,” she lowers her chin, looks at me beneath raised eyebrows, winks at Gary. “But you get other folks too, cheapies, like this one.” Gary grins back. Years come off him.

The two thousand pounds Gary spent on his boat is a pittance, especially if you consider the expense covers both accommodation and transportation for three months in the country. The solar panel and electric motor he rigged up means he pays nothing for fuel. I know he’s lived for the last forty years on his family farm in Eureka and if he’s like my uncle he’s got gold ingots buried in his back yard. But how much cash is at his disposal? It’s not an easy question to ask on a first date and really beside the point.

What I really want to know: if he has the means to travel more comfortably, why not? Why piss in a pot?

Choosing candor over tact I ask him. We’ve returned to the boat and motor upstream to a secluded spot, protected from the wind, where Gary will moor for the night. We sit across from each other in the open back, knees all but touching. I close my eyes and feel the touch of shadows and sunlight on my face. Under the bird song, I hear the burble of the electric engine and the gentle slap of water against fiberglass. Gary waves to a young fat couple on a bench, and they don’t wave back. The wind has risen. Spears of sunlight pierce the gathering clouds. Swans, swimming alongside, outpace us. I feel no impulse to take notes, or to check my phone. After a few more minutes that chattering voice inside me, the list-maker, task-setter quiets. When Gary speaks again, I’ve all but forgotten my question.

“I graduated, all that,” he says. “Got a job with an engineering firm. Good job. Five years in, I left and bought this boat.” He pauses, running bony fingers across the hull. “Spent ten years sailing. The Great lakes, the Mississippi, up the eastern seaboard.”

“Wait. What?” I say, pulled from my reverie. This new information splinters my simple judgment of him. “Ten years. You spent ten years…on this boat?”

“Same model. A Vivacity 20. No solar panels, course. Looked everywhere on-line for one just like it and here she was,” he pats the padded bench. ‘“Misty, in England.”

I had assumed England or simply the canals had brought him here. But these were secondary destinations. Looking off into the distance, beyond the fields, his expression now is one of unguarded wistfulness. I see the young man beneath the beard: pale face flush with color. For a moment, muscle fills out his hollow chest. In the sudden gust of land locked wind, I smell the sea, and I know Gary is stranded somewhere between this place, this time, and another time and place every bit as vivid in his memory. If I’d been outside myself, outside of time, I’m now stranded here with him in this suspended moment of melancholy, which breaks with the sound of the church bell chiming three.

Three! I look at my watch, and Gary, the spell broken, notices. Ducks flap away in a ruckus. “Your uncle’s cabin, in Washington,” he says. “I think that’s when I saw you last.” I remember the cabin. I don’t remember Gary. It’s thirty three years ago, and yesterday. “You were rushing around then too, weren’t you? Pigtails flying. Going where?” But he’s not looking at me anymore; his hand on the throttle, his eyes on the slow passing landscape. “Going where?”

I sit for a long time in my car after Gary walks me back to town. Watch him disappear up the road, comically out of place in stained Levis and flannel, saying “hi there!” “hello,” to any passing Brit. Out of place, yet perfectly at home in that English town. I sit there, though I haven’t asked half the questions I should have, were I to write a story. Sit there even though I’ll be home late, overcome by gratitude for this glimpse of a traveling life and vision of peace I didn’t know I’d been seeking.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed