The Divide

After the Civil War, the women's suffrage movement split into two factions over the 15th Amendment. In its final form the 15th Amendment promised that the "right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." No mention was made of gender. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and their following were terribly offended by this omission. They assumed that the rights of women would be championed alongside the rights of black men and they opposed the Amendment on the basis of women’s exclusion. Other reformers like Lucy Stone and Mary Livermore, though not happy, supported the amendment anyway. They feared, as did a number of male legislators, that if women were included, the amendment would not pass and no new suffrage rights would be won. And surely, they thought, the tide of change was upon them! Surely it would be only a matter of years before women, too, won the vote.

Five contentious, frustrating decades passed before women won the vote in federal elections. Not one of the women of the Seneca Falls generation lived long enough to enjoy the right.

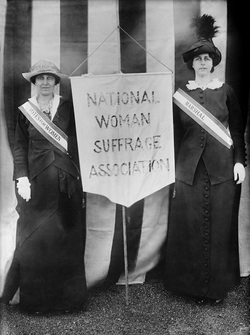

I don’t know if the omission of women from the fifteenth amendment was, as Stanton argued, an unreasonable or unnecessary compromise. Some scholars argue that the rise of Jim Crow would have been curtailed if women had had a voice in politics, but this implies that women (white women really) were, as a group, more progressive and open minded than men. I’m not sure this was, or has ever been, the case. What is certain is that the split of the women’s rights movement into two feuding contingents -- the National Women’s Suffrage Association and the American Women’s Suffrage Association -- stunted the movement for years.