Dates: 4 Wednesdays, September 21 - October 12

Time: 6 - 8 pm PST

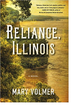

Instructor: Mary Volmer

Format: ZOOM

Genre: Nonfiction (Fiction Writers and Poets Welcome!)

Price: $275

Enroll

Sports are a vital part of western culture, yet we rarely reflect upon, much less write about, how sports have influenced our lives, our families, or our communities. In this four-week writing class, we will use sports as a lens through which to study and write personal essays.

Fear not! You don't have to be an athlete, has-been or otherwise, to join us. We will be exercising our literary muscles with daily craft talks and guided writing prompts. Together we will learn about essay structure, voice, pacing, scope, and audience. And we will read and discuss excerpts of longer works by poets, novelists, and memoirists such as Natalie Diaz, Pat Conroy, Reginald Dwayne Betts, Lucy Jane Bledsoe, John Edgar Wideman, John Updike, and Sue Hyon Bae.

With these diverse authors as our guides, we will write about our own complicated relationships to sport. How do sports affect our self-image and self-worth? Are sports a religious activity? A patriotic activity? A selfish or a selfless activity? What is a “team player”? How do we view race, gender, and sexuality through the lens of sport?

Join us and write personal essays inspired by sports.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed